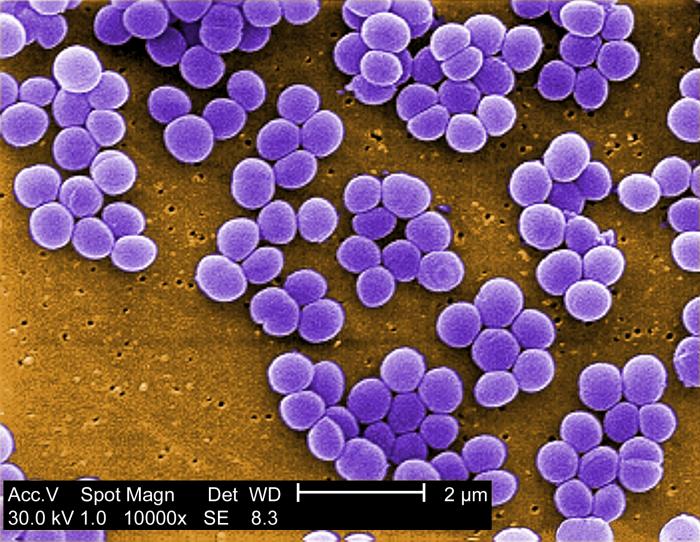

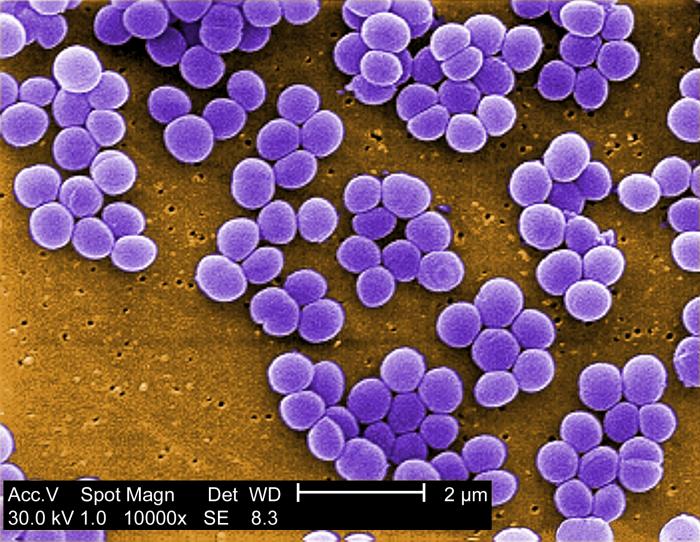

Image courtesy CDC/ Matthew J. Arduino, DRPH

This is a false colour scanning electron micrograph.

Some of the cells can be seen to be preparing to divide. Staphylococci tend to cling together after dividing in different directions and so resemble a bunch of grapes.

To a bacteriologist, Staphylococcus aureus is a facultatively anaerobic Gram-positive coccus.

When cultured on blood agar it exhibits haemolysis and it tests coagulase-positive and catalase-positive.

Image courtesy The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University of Copenhagen

On this blood agar plate

Staphylococcus aureus colonies show whitish grey and glistening.

Mouseover to see zones of haemolysis, visible when lit from below.

Staphylococcus aureus may cause minor skin infections such as pimples and boils, but these may become deep-seated, causing abscesses etc.

If it enters the blood it can cause a number of problems in the body:

bacteremia and

sepsis,

toxic shock syndrome (TSS),

pneumonia,

meningitis,

osteomyelitis,

endocarditis.

Some strains produce (entero)toxins which can cause food poisoning.

Staphylococcus aureus is likely to cause problems in hospital patients:

- pressure sores due to inactivity in bed

- surgical wounds after operations such as hip replacements or heart surgery

- being treated with intravenous drips or urinary catheters

All of these offer opportunities for bacteria to enter the body from the skin surface and cause infection.

Image courtesy CDC/ Bruno Coignard, M.D.; Jeff Hageman, M.H.S.

This is a cutaneous (skin) abscess on the hip of a prison inmate, spontaneously releasing its contents as pus.

Image courtesy CDC/Dr. Mike Miller

This is a photomicrograph of

Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria, grown in a liquid medium containing blood.

It is a gram-stained preparation, seen using a light microscope. The bacteria can be seen as purple dots in short rows, and the pinkish strands are fibres of fibrin in the clotted blood.

Initially this organism was known as

Pneumococcus, then renamed

Diplococcus pneumoniae because it was commonly seen as pairs of cells in sputum from people infected with pneumonia. When grown in liquid media in the lab it forms chains so it is now known as

Streptococcus pneumoniae.

It was first isolated and described on 1881, by two pioneers of bacteriology working independently of one another: Louis Pasteur in France and George Miller Sternberg in America.

This organism was used to show the significance of DNA as the carrier of genetic information when the 'transforming principle' passed from a virulent but killed strain of bacteria (a 'smooth' form, with a capsule) to a non-virulent strain (a 'rough' form, with no capsule), as shown by experiments on mice. This transformation, discovered by Frederick Griffith in 1928, was proved in 1944 by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty to be caused by DNA not protein.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram-positive, catalase-negative coccus. It is said to be an aerotolerant anaerobe. When grown on agar containing blood it shows

alpha haemolysis

Klebsiella spp. as seen under the light microscope

Klebsiella species are

nonmotile,

rod-shaped,

gram-negative,

catalase-positive,

oxidase-negative,

lactose fermenting,

facultatively anaerobic

bacteria with a prominent polysaccharide

capsule.

The genus Klebsiella is named after Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs, a German-Swiss pathologist and microbiologist who identified the bacterium causing diphtheria.

Klebsiella pneumoniae ferments lactose

Klebsiella pneumoniae ferments lactose and produces pink colonies on McConkey agar. The shiny (mucoid) colonies indicate the presence of the capsule.

Image courtesy CDC/ National Escherichia, Shigella, Vibrio Reference Unit at CDC

Image courtesy CDC/ National Escherichia, Shigella, Vibrio Reference Unit at CDC

This is a colourized scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicting a number of Gram-negative

Escherichia coli bacteria of the strain O157:H7.

Escherichia coli is widely known as

E. coli, although scientific names should not be abbreviated until they have been stated once in full.

In the past it has been called

Bacterium coli and

Bacillus coli, but it was (re-)named after Theodor Escherich, a leading German bacteriologist in the field of paediatrics, who first described it in 1886. The specific part of the binomial name "coli" means " of the colon" - the large intestine (also known as the bowel).

It has been widely used in laboratories for over 60 years because it is easy to grow and offers little danger of infection, and it has been extensively used in virology and recombinant DNA work.

As it leaves the body in faeces and can survive for some time afterwards, it serves as an indicator of faecal contamination of the environment and foods.

A number of microbiological test procedures have been developed for this purpose. It lends itself to tests involving selective media based on recreating conditions within the colon.

It is a Gram-negative,

facultatively anaerobic,

rod-shaped bacterium. It is non-sporulating i.e. it does not produce spores.

Some strains are motile i.e they possess flagella, which are described as peritrichous i.e. projecting outwards all round the surface of the cell wall.

Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli as seen under the light microscope

Image courtesy CDC/ Janice Haney Carr

This is a monochrome (uncoloured) scanning electromicrograph.

Enterococci are facultatively anaerobic Gram-positive cocci. In culture media they do not show haemolysis.

The most clinically relevant of these bacteria are E. faecalis and E. faecium.

The term enterococci may be used in a general sense to mean round-shaped bacteria (cocci) found in the gut, but if used as a Genus (Enterococcus spp.), it should be italicised.

They were previously categorised as "Group D" Streptococcus organisms.

Image courtesy CDC/ Janice Haney Carr

This is another false colour scanning electron micrograph.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa - also known as Pseudomonas pyocyanea - is a Gram-negative, aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium. It is motile. When grown on certain types of agar in the laboratory, it produces green pigments.

The genus name Pseudomonas means 'false unit', although it might be an attempt to distinguish it from another organism living in water, probably a protoctistan. The species name aeruginosa refers to the blue-green pigment produced in culture.

Image courtesy CDC/ Lois S. Wiggs & Janice Carr

Clostridium difficile is a

Gram-positive,

anaerobic spore-forming rod-shaped bacterium.

Its specific name (difficile) - meaning difficult - may be pronounced in a number of ways, depending on different styles of Latin or even French.

Being anaerobic spore-formers, Clostridium species are in a category of their own. They also produce toxins which have adverse effects on the human body.

Other members of the genus Clostridium cause tetanus (jockjaw), botulism, and gangrene.

Most bacteria form only vegetative cells, and although they grow quickly and can cause different sorts of problems inside the body, outside the body they are easily killed by exposure to reasonably high temperature, dry conditions, and certain sorts of chemicals - antiseptics and disinfectants.

The spores formed by Clostridium species are extremely resistant to these conditions, and remain viable for months or years. In fact these spores can withstand exposure to high temperatures and strong disinfectant chemicals.

As anaerobic organisms, they can cause problems within the body as they can respire, function and reproduce in parts of the body that are not well supplied with oxygen, such as in the gut or deep within muscles.

Background information

Clostridium difficile bacteria are naturally found in the gut of some people, probably kept under control by the activities of other harmless bacteria there - it may be called

commensal. Some cells of

Clostridium difficile are transformed into spores, which will leave the body in faeces and on underclothes and bedclothes, but presumably these do not cause any further problems for these people. The spores of

C. difficile can survive in the environment in a state of suspended animation for months or years.

Disease caused by Clostridium difficile

In the hospital or other healthcare environment spores may be spread from one patient to another, perhaps when bedclothes are changed.

Spores of

Clostridium difficile entering the body can germinate and the resulting vegetative bacterial cells can grow in number. This may cause flu-like symptoms or (mild?) colitis.

However, if antibiotics are administered, they may eliminate other competing micro-organisms in the gut, causing unchecked growth of C. difficile.

In this context cephalosporins and in particular quinolones and clindamycin

are considered to be high risk antibiotics.

Growth of C. difficile may cause more severe diarrhoea - the condition being known as antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD). Toxins from C. difficile can cause severe inflammation of the colon - pseudomembranous colitis may result. This may be treated using completely different antibiotics.

Antibiotic Resistance problems

Clostridium difficile strains resistant to clindamycin and to fluoroquinolone antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) have been reported in the USA.

Elsewhere

on this site

are pages covering topics relating to this one:

Web references

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

E. coli: Are the bacteria friend or foe?

Before antibiotics were discovered, Staphylococcus aureus infections were frequently fatal.

Originally Staphylococcus aureus bacteria were easily killed by penicillin, as shown by the zone of inhibition on this Petri dish from Alexander Fleming in 1928.

Before antibiotics were discovered, Staphylococcus aureus infections were frequently fatal.

Originally Staphylococcus aureus bacteria were easily killed by penicillin, as shown by the zone of inhibition on this Petri dish from Alexander Fleming in 1928.